Flies and Cancer research: an old unlikely partnership

26 Chwefror 2015

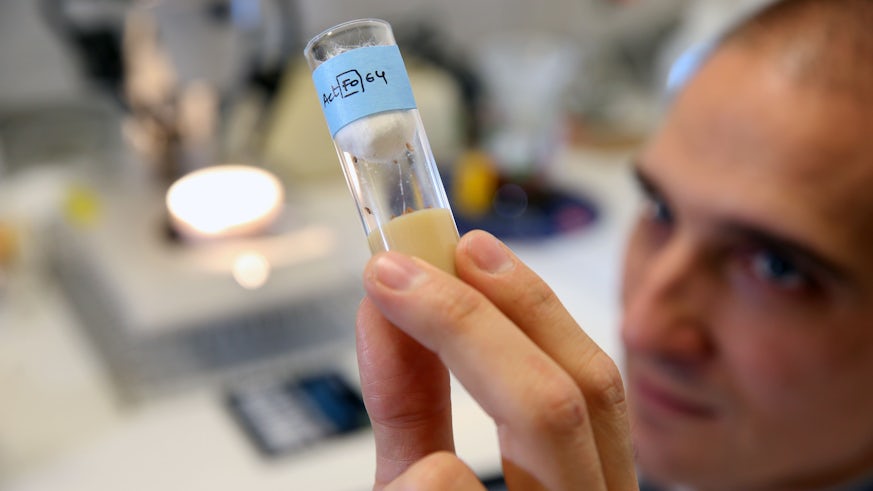

Research Fellow Dr Joaquín de Navascués has been affectionately dubbed the 'Spanish fly man' by visitors to the Institute. He explains why a practice that is over a century old is still at the cutting edge of cancer research.

When I joined the Institute I noticed how enthusiastic people are about communicating their science. Lab visits are very popular, and soon I had people at my "lab doorstep" keen to hear about our work. I focus my research on the underlying competition between stem cells within tissues, which I think is important for cancer initiation – a challenge to explain.

Lab tours became an introduction to the use of Drosophila, the fruit (or rather, the vinegar) fly, in research. Visitors were always surprised to know that more than half the human disease genes have an equivalent in Drosophila; that flies are used to understand the function of human genes.

I remembered when in 2008 Sarah Palin, then candidate for Vice-President of the US, dismissed research in fruit flies as "having little or nothing to do with the public good". This was an embarrassingly misinformed comment for someone in her position, which earned her a rather vitriolic response from the media. However, I can see why that seems a natural stance to take for a citizen without exposure to Drosophila research.

Working with Drosophila is fast and cheap, which produces scientific answers on virtually any general biological problem. Since the first Drosophila cultures were established c. 1910 it has made key contributions in biology – such as finding the first tumour suppressor gene in 1967. Discoveries in the fly have been rewarded with five Nobel Prizes, three of them of essential medical impact: the chromosomal basis of inheritance (1933), the mutagenic capability of ionizing radiation (1946) and the molecular basis of innate immunity (2011). Signalling genes and transcription factors as important as hedgehog, porcupine, frizzled, or Notch owe their names to the anatomical defects observed in the corresponding mutant flies, either in the larva or the adult. Beyond genetics, the fly is becoming a serious platform for drug screening, providing the advantages of using a whole organism with a digestive system.Of course, a model organism with an open circulatory system and lacking breasts, prostate, or lungs (flies have a rigid tracheal network) has important limitations. It is still possible, however, to study in the fly genes associated with specific human cancers. We can introduce those genes in the fly and find an organ in Drosophila where they produce a cancerous pheno-type. Indeed, we are working alongside two other labs in the Institute, to develop Drosophila models for gene functions that are known to be important for breast and prostate cancer, but whose functional details are largely unknown, and costly to pursue in mouse models.

Drosophila has a long history of research in biomedicine, and its capabilities as a model organism are being expanded and updated every year. It is an exciting and fundamental model to work with, which could transform the way research into cancer develops in the future.