Opening a can of worms

7 Medi 2016

New findings suggest that otter parasites are not invaders after all

While conducting routine otter post mortem examinations in Cornwall in 2005, vet Vic Simpson noticed abnormal thickening of otter gall bladders, and eventually identified the trematode worm Pseudamphistomum truncatum, never previously reported in the UK. Concern was raised by ecologists and conservationists about the origins of this parasite and its potential to harm otters. Cardiff University Otter Project have been investigating P. truncatum for the past nine years and have opened a real can of worms!

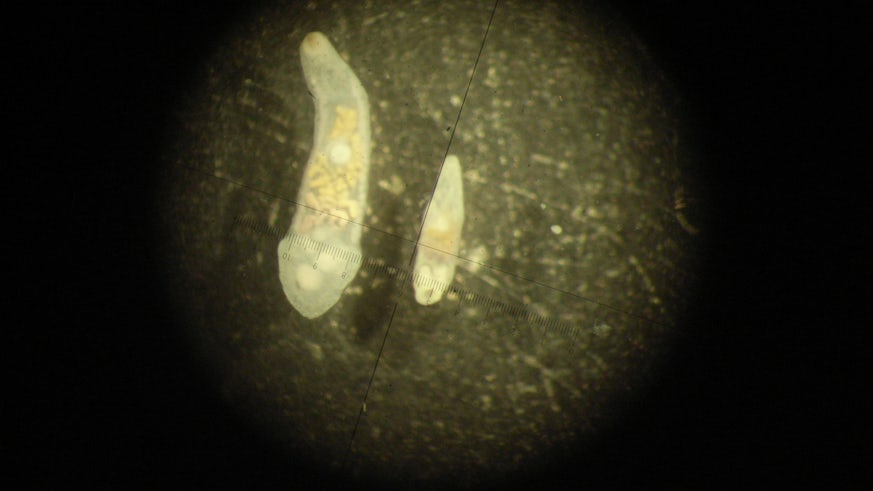

Helped by funding from the Environment Agency, the Otter Project screened gall bladders from 273 otters across England and Wales. Leading that work, Ellie Sherrard-Smith found 12% had P. truncatum, largely in otters from the south. What was really intriguing though, was that this screening unveiled a second, larger worm in the gall bladder of some otters, mostly from East Anglia. Identified morphologically and confirmed by Natural History Museum, London as Metorchis albidus, this species had also never been reported in the UK. Several questions arose – were these parasites new to the UK, or had they gone undetected for years due to lack of systematic screening? If new, where had they come from, and were they spreading? And importantly – were they harming the UK otter population? With PhD funding from NERC and Somerset Otter Group, Ellie spent the next few years trying to answer these questions, and others.

Our latest findings came as something of a surprise. Ellie worked with collaborators to source specimens from across Europe, in order to try and shed light on the genetic origins of the UK specimens. Petr Heneberg's group at Charles University in Prague then gave us a bombshell… what were previously recognised as three different species, with slightly different morphologies and found in different hosts, were in fact one and the same. M. albidus (from otters), M. bilis (from great cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo) and M. crassiusculus (from eastern imperial eagle Aquila heliaca and long-legged buzzard Buteo rufinus) represent a single species, and as M. bilis was historically the first to be identified (in 1790) this name takes priority. Infection arises when these vertebrate hosts (birds, or mammals) eat infected fish prey.

The identification of parasite species can be very challenging, and molecular techniques are providing major advances to this field. While taxonomy can seem a bit of a ‘dry’ topic, this has major implications for our understanding of the potential origins of these parasites. While ‘M. albidus’ (as was) and M. bilis had not been confirmed in the UK previously, M. crassiusculus has – frequently, in birds. So this species can now be presumed native in the UK, and has probably been infecting otters for many years. No such helpful clarification for P. truncatum – but genetic comparisons for this species across Europe suggest that it is probably also a long-term resident of the UK.

Are these parasites a concern for otter health? From current evidence, it does not appear that they are causing harm, apart from in a small number of individuals with very heavy burdens. However, our data is mostly from road-killed otters, which are mostly young males. This is important to consider – older otters have more parasites so we could be under-estimating overall parasite loads. Our research has also shown that non-native American mink can be infected by P. truncatum and can potentially spread around 3 times as many parasite eggs as otters, so changes in mink distribution and abundance also has implications for parasite dispersal.

There is no room for complacency: CUOP data shows an increase in the numbers of parasites per otter each year, something that may be associated with changing climate. If this trend continues we could start to see effects on the UK otter population. For this reason we are seeking funds to repeat screening of otters that are sent to Cardiff.

Dr Ellie Sherrard-Smith completed her PhD research at Cardiff University on otter parasites and has published her findings, see list on right and:

- Sitko J, Bizos J, Sherrard-Smith E, Stanton DWG, Komorova P, Heneberg P et al., (2016) Integrative taxonomy of European parasitic flatworms of the genus Metorchis Looss, 1899 (Trematoda: Opisthorchiidae), PARASITOLOGY INTERNATIONAL, Vol: 65, Pages: 258-267.