Studying the scientists

17 February 2016

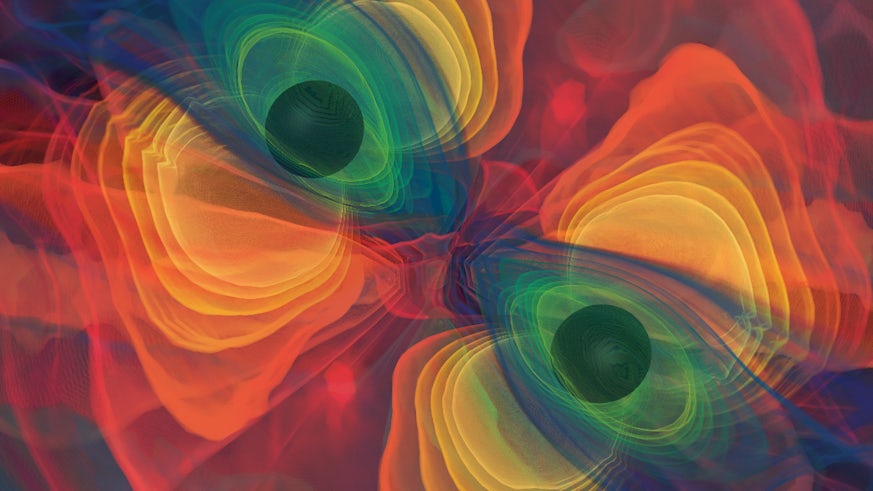

You no longer need to be an astrophysicist to be interested in gravitational waves. Since their existence was finally confirmed, these hard-to-detect ripples have been making headlines all around the world. And rightly so – it’s an incredible scientific discovery, one hundred years in the making, that has opened a new window onto our understanding of the universe.

For the past fifty years scientists, including colleagues at Cardiff University, have worked to prove that gravitational waves, first posited by Albert Einstein a century ago, actually exist.

During this half-a-century of determined scientific effort, one person has been there almost from the beginning, dedicating 43 years to following the enterprise. He’s attended almost every important conference on gravitational wave research, presented to the Gravitational Wave International Committee, and several of his books on the subject are included on LIGO’s reading list for anyone interested in the discovery.

He’s not a physicist though. He’s Professor Harry Collins, a Distinguished Research Professor at the School of Social Sciences, and he started his journey in 1971 with the chance reading of a New Scientist article on the detection of gravitational waves. He’s been studying the gravitational wave community ever since and his work is helping to enhance our understanding of the nature of science, scientific consensus, how our society makes knowledge, and the place of science at the heart of the process.

Professor Collins said: “I’m a sociologist of knowledge, and just happen to study science to see knowledge being formed.

“I’m proud to be nearly the last man standing from the era that marked the beginning of the search for gravitational waves. I’ve spent a lot of intervening years wondering if I will actually live long enough to see the waves detected so, now that the discovery has been confirmed, I’m thrilled for my scientific colleagues. But I’m a social scientist, not an astrophysicist, and I differ from these colleagues in that for me, the confirmed discovery – although a proud and happy moment – has possibly been the least interesting part of the entire process.

“In tracking the progress of the science of gravitational waves, I’ve been able to use my first-hand observations of the physicists and their internal culture to better understand the meaning of scientific knowledge, the nature of expertise, how we use science as a tool to arrive at truth, and what happens when scientists disagree.

“For example, science works on theories and evidence. The commonly held lay assumption is that, unlike the humanities, there is only ever ‘one right answer’ in science. But nothing is ever that straightforward! Science is beset with uncertainties and yes, scientists do disagree with one another. It’s been fascinating to explore the nature of scientific consensus from within the often-controversial field of gravitational waves. For years, my colleagues working on the search have had to contend with scepticism from other parts of the scientific community, as well as come to terms with the fact that numerous past claims to have detected waves failed to survive scientific scrutiny.”

Gravity’s Ghost: Scientific Discovery in the Twenty-first Century, Professor Collins’ 2004 book, recounts an incident when signals potentially thought to be been evidence of a gravitational wave turned out to just be a signal test. Having learned that it was not a real signal, the scientists simply moved on with their work. But it had a much larger impact on their team sociologist.

“From this process the scientists learned how to do data analysis better, and they learned how hard it would be to convince themselves that they’ve seen evidence of a gravitational wave in future tests. It quickly lost its importance for the scientists but to me, the lessons about how scientists argue and make knowledge have been lasting ones.

“At the heart of scientific consensus there’s usually a point where decisions are made in a much more commonsensical or philosophical way. Science is made by common sense, and not just by calculation.”

After 40 years of studying the scientists, what happens now that they’ve finally provided the world with conclusive proof of what Einstein had suspected all along?

Having learned of the potential discovery back in September 2015, Professor Collins has been working on a follow-up to his books chronicling the search from the beginning.

“I have always said that, should I live to see waves detected, I would write a fourth book on the subject. And that is exactly what I have been doing (in secret, of course, to respect the announcement embargo). Gravity’s Kiss: The Detection of Gravitational Waves will be the culmination of my decades in the field and I am profoundly grateful to the community for letting me share their secrets and treating me as one of them.

“There will be several themes in this book – how controversy in transformed into consensus and how even a discovery as sure as this one is based on social conventions of what counts as truth, who you trust, when you stop questioning and what you take for granted.”