100 years on, poet’s “bloodless death” mystery solved

19 October 2017

The famed “bloodless death” of a landmark British poet in the Great War has been investigated by experts from the Humanities and Sciences a century after his death, in a new project undertaken at Cardiff University.

Biographical and critical works about Edward Thomas (1878 – 1917) often refer to his “bloodless death”, a story that emerged following his death aged just 39 at the Battle of Arras on Easter Monday in 1917.

Letters from Thomas’ widow Helen claim that his body was left without obvious injury. But letters, held in Cardiff University’s archive, sent to Helen from Thomas’ fellow officers contradict this view, reporting that he was killed by a direct hit from a shell. Despite the contradictory evidence, Thomas’ “Bloodless death” has continued to inform perspectives on his life and work.

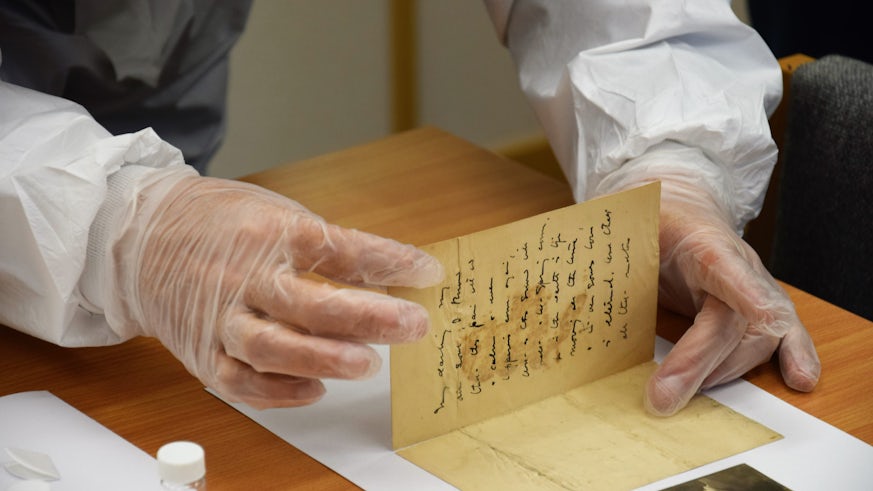

With access to Cardiff University’s Special Collections and Archives – home to the majority of Thomas’ writing – Dr Carrie Smith of the University’s School of English, Communication and Philosophy set out to understand this mythology further, by examining the poet’s extensive archive, both its texts and its material objects. In Thomas’ personal effects, Dr Smith discovered a potentially significant letter, believed to be among the items found on Thomas’ person when he was killed. This letter showed clear signs of staining, which could potentially have been blood.

To examine this more closely, Dr Smith assembled a team of experts from the Humanities and forensic science. The team included Professor Martin Willis of Cardiff University’s ScienceHumanities initiative, Alan Hughes, Head of Special Collections and Archives, as well as forensic scientists Nigel Hodge and alumna Abigail Carter, from Forensic Resources Ltd, a company founded by Carter.

Although the stained letter gave no result, perhaps due to its age and deteriorating condition, a photograph accompanying the letter did test positive for blood. Whether this was the blood of Edward Thomas, or came from another soldier on the front line at Arras, the forensic scientists could not say.

Dr Smith explains the significance of the research and the discovery: “Our research tells us more about the cultural mythologies of soldier deaths in World War One. In Thomas’s case, his widow’s recounting of her husband’s body as ‘untouched’ in death seems to be the result of her conflating two accounts: one account from the day before he died of a dud shell landing near him, knocking him off his feet but not exploding, and another the report of his death by direct hit from a shell the following day. The letter and the photograph that were on his person when he was killed have marks from the percussive strength of the shell blasts..."

"It is sobering to be reminded that documents have their own lived histories and can reveal material evidence of conflict and suffering."

Professor Willis, also of the School adds: “The First World War remains such a big part of our collective cultural memory and this research both reinforces that and adds to it in interesting new ways. It is not uncommon to use contemporary science to find out things about the past but it is unusual to link together a poet and forensic science. For us as academics it is exciting to work across the disciplines of the Humanities and Sciences to add to our cultural and historical knowledge.”

The investigation process is captured in a 30-minute podcast and series of photographs, on the ScienceHumanities website. The world’s largest Edward Thomas archive remains available to scholars at the University’s Special Collections and Archive.

Penning all his poetry in the last few years of his life, writer Edward Thomas is recognised today as a major but overlooked figure in modern poetry. He lived only to see one book of verse, Six Poems, in print. Thomas is permanently remembered at Westminster Abbey’s Poets Corner.